I’m still asked whether or not poetry should rhyme – a question not to be dismissed, although evidence is there that it needn’t in the great Americans of the 19h and 20th Centuries: Whitman, Carlos Williams, Sylvia Plath. In the long, speech-based rhythms of the first, the page-as-artistry of the second and the shock-sequencing of the third, there is poetry enough. You don’t have to be a rhymester as well as a poet in order to be great.

And yet. A rhyme-scheme is part of a rhythmic whole. It is a balance in recitation and is integral to a public perception of poetry. For many readers and audiences a work is not admissible unless it has that trademark, signifying artistic use of language. For performance poets, many of whom recite without text, rhyme is a mnemonic, as for those who learn poems by heart.

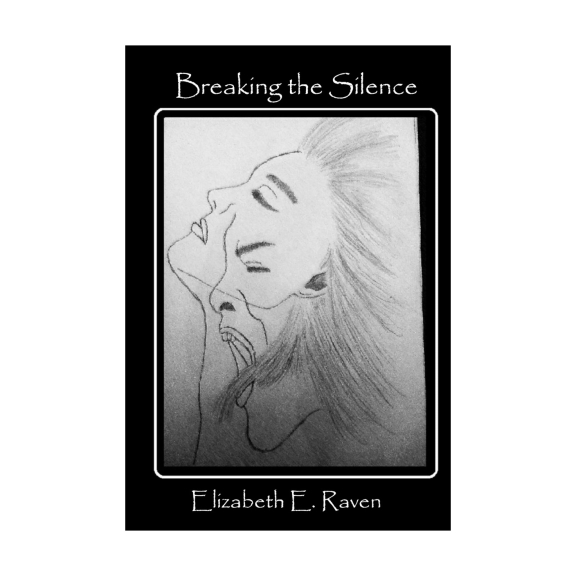

Raven, the name under which this poet has chosen to write, already suggests the dark and unspoken, Breaking the Silence an emergence from those shadows. But what shadows. The collection enacts the first utterance, the bringing-to-light, of a totally controlling relationship. This is pictured through monochrome photographs where the victim’s face bears the handwritten labelling of the abuse, and carefully hand-drawn images. A woman, arms held high above a graceful form, a dance perhaps. The viewer is then shocked to see the actual brutality of the depiction: strings are attached to every limb and we know the freedom to be illusory. She is at the mercy of the puppeteer.

I used to dance with joyful grace,

Now stumble blindly in this place

He holds the strings, he makes me sway,

And steals my spirit day by day.

Puppet on a String

And property of. The book chronicles an early hopeful marriage, soon to be replaced by subjugation. This onslaught, through domination of will initially, progresses to violent language and to violence itself. The abuse taking place behind closed doors.

The delivery through rhyme cements the perception of this as something created, a form of ‘storying’, close cousin to a song. The terrifying scenes that Raven sketches, both graphically and through words, are mediated by the verse-form. This is not autobiography. It is poetry.

A piece of meat upon a butcher’s slab

Or to be prodded at like a mouse in a science lab,

Made to your design, a creature to create,

A robotic, makeshift wife to replicate …

Artificial Intimacy

The rhyme here moves the sequence of images forward. I have a sense that the first one, the ‘butcher’s slab’ has through rhyme beckoned in the second, less familiar, of the scientist’s laboratory. Forward again to that most notorious of the profession, Dr Frankenstein, where the ‘piece of meat’ suffers something worse than death. The ‘creature to create’ has been denatured from its original pure and good form. The stanza begs the question – how does the self survive after such treatment?

The collection leaves the question unanswered, but in an open-ended way. The Battered Wives’ Club and the prose-writing that follows point to the solidarity of survivors and the writing of poetry as agents in recovery. The later poems, some of the best, speak of coming to terms with the experience, and even pity for the torturer.

In the deepening dusk of our shared sorrow

I wonder who I am becoming,

the shadow of a girl who forgot

how to bloom beneath the sun.

Kiss and Tell

These time-references, of noon falling away to night, point to the finite nature of our lives, to years now unrecoverable, and to acceptance of that loss. Raven now chooses a looser verse-form, for these are larger, more philosophical expressions, of a poet moving beyond narrative. The ‘I’ in the poem stands for all of us, taking stock of our pasts, becoming reconciled, and wondering now how to live.

Presenter Black Country Radio & Black Country Xtra

Solicitor - Haleys Solicitors

The following Cookies are used on this site. Users who allow all the Cookies will enjoy the best experience and all functionality on the site will be available to you.

You can choose to disable any of the Cookies by un-ticking the box below but if you do so your experience with the Site is likely to be diminished.

In order to interact with this site.

To show content from Google Maps.

To show content from YouTube.

To show content from Vimeo.

To share content across multiple platforms.

To view and book events.

To show user avatars and twitter feeds.

To show content from TourMkr.

To interact with Facebook.

To show content from WalkInto.